The Peace Arch Historical State Park in Blaine, Washington and the Peace Arch Provincial Park in Surrey, British Columbia occupy the same tract of land. Visitors to this 43-acre transitional space can enter from either the United States or Canada and freely commingle amidst the manicured lawns “without passing through a port of entry.”1 While it is wise to carry identification, if you stay within the confines of the park, passports and other documentation have traditionally been unnecessary.

The focal point of the park is the Peace Arch, a distinctive 67-foot neoclassical archway that spans the borderline dividing the two countries. It stands firmly and eloquently as a symbol of international cooperation. An inscription on the interior of the monument commemorates the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812. This treaty restored peace and amicable relationships between the United States and Canada (then Great Britain) and established commissions to reexamine national boundaries. Other inscriptions, such as “Children of a Common Mother,” emphasize unity and coexistence, suggesting that “the the highest goal between great nations should be perfect peace.”2

The creation of the park was a communal effort. The archway was commissioned by U.S. financier and humanitarian, Samuel Hill, who yearned for world peace. “In a letter written to Samuel Hill and read at the Peace Arch dedication ceremony [in 1921], President [Warren J.] Harding praised the creators of the portal. According to Harding, all of humankind could look to the U.S./Canadian border as a model for peace and as a sign of global progress.” 3 By 1930, children in both countries had donated almost 4,000 dollars to purchase and to improve the land around the monument. With the addition of state and provincial funds, the entire joint-park project, including its rose gardens, kitchens, and picnic shelters, was officially completed in 1939. Ever since then, it has been a regional, transnational gathering place, with annual events such as the Hands Across the Borders Celebration.

Inexplicably, however, in early 2025, the U.S./Canadian border became viewed by members of the Trump administration as a contested space. At an Oval Office press conference on March 25th, President Donald Trump referred to the border between the United States and Canada as “an artificial line, that straight artificial line that looked like it was drawn by a ruler; I don’t mean a ruler like a king, I mean a ruler like a ruler. It’s just an artificial line that was drawn in the sand, or in the ice.”4 To suggest that the northern border between the United States and Canada is an artificial line is misleading, dismissive, and hypocritical.

Borders Are Intentional

Borders between states and countries can be natural or political; the latter created through binding legal agreements. For example, in Washington state, the Pacific Ocean and the Strait of Juan de Fuca are natural land features that form the border to the west. The Columbia River is a natural land feature that forms a partial border to the south.

The political boundaries of states such as Washington are artificial in the sense that they are manmade. However, the word artificial has many negative connotations such as fakeness or disingenuousness. These do not apply to political borders since they are not arbitrary divisions.

Washington state’s political borders were scientifically and geometrically determined. While it might be an accurate observation to describe political boundaries, particularly in midwestern and western states, as appearing to have been drawn by a measuring tool such as a ruler, they follow a grid-like system by design rather than caprice. These lines are the result of federal surveys conducted by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and correspond to cartography lines of latitude and longitude. Furthermore, they adhere to federal policies such as the Land Ordinance of 1785, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, and various homestead acts in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A close examination of a map of Washington state reveals that the southeast corner that forms the boundary between Oregon and Washington exactly follows the 46th parallel. To the east, the boundary between Idaho and Washington falls directly upon the 117th meridian. Crossing these boundaries makes one subject to different laws, different civil jurisdictions, and in some cases, differing cultures and ideologies.

International Borders are Covenants Between Sovereign Nations

The same holds true for international political boundaries. “The Canada-United States border is the longest international border in the world at 5,525 miles. There are more than 100 land border crossings between Canada and the USA.”5 The evolution of this international border is complex because the history of the two countries has been intertwined since America’s founding. Starting with the Treaty of Paris in 1873, which ended the Revolutionary War, each stage of U.S. expansion required border negotiations. Borders are mutually agreed upon, and according to international law cannot be unilaterally dissolved.

Between 1873 and 1909 there were at least seven treaties that affected the U.S.-Canadian border. Both the Treaty of 1818 and the Oregon Treaty of 1846 effectively established the international boundary between the United States and Canada at the 49th parallel. The Treaty of 1818 established the border from the east to the Rocky Mountains, while the Oregon Treaty established the boundary west of the Rockies.

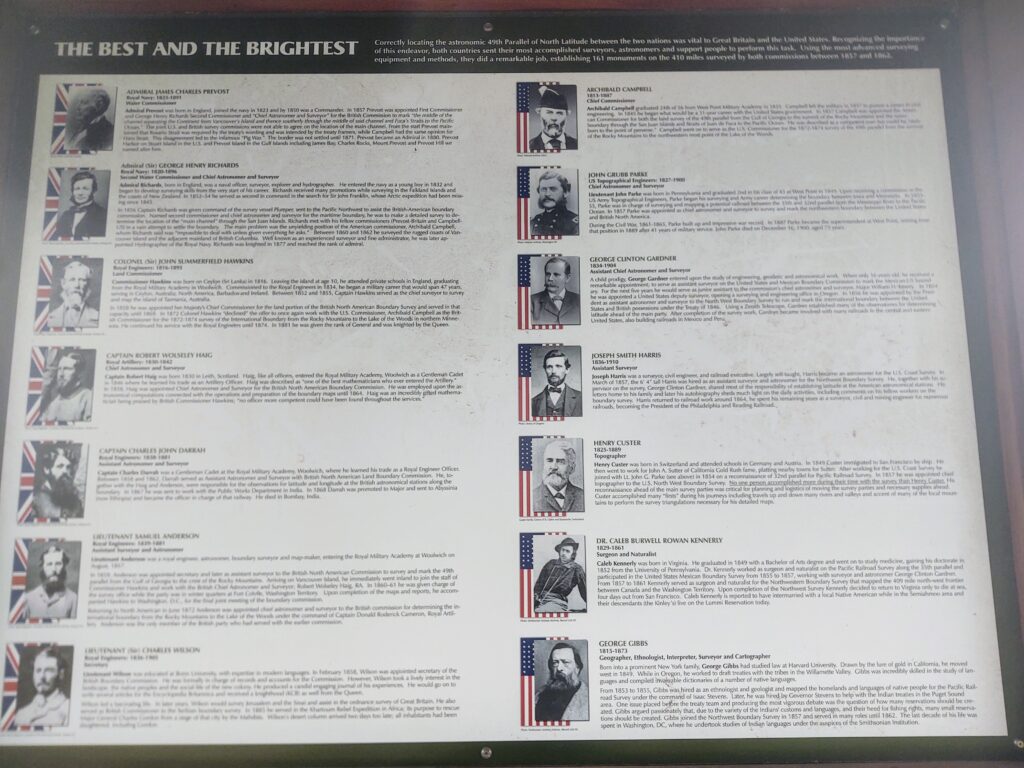

Beginning in 1857 and lasting until 1862, commissions from both countries, consisting of teams of astronomers and surveyors, undertook the arduous task of ascertaining the border and erecting 161 survey monuments to mark its location. The U. S. Northwest Boundary Commission included gifted scientists such as Archibald Campbell, the chief commissioner who was a career civil service engineer; John G. Parke, the chief astronomer and surveyor who later became a Civil War hero and a superintendent at West Point; and topographer Henry Custer, whose extensive travels and documentation, particularly in the North Cascades, greatly added to the geological record. In all, nearly two hundred men were required to support the survey parties.

These scientific commissions calculated each geographic position astronomically. “Latitudes were determined with the zenith telescope [which helps establish latitude]; azimuth and time with the transit [meaning that altitude and sun and moon angles were a factor in finding coordinates]. Longitudes were determined by chronometer [a mechanical timepiece], by moon-culminating stars [stars that reach the meridian along with the moon], and at one station, by solar eclipse.”6 The accuracy of their work, done without current technologies such as computers and global positioning systems (GPS), should be honored as remarkable feats of engineering.

In Washington state, the work of the U.S. Northwest Boundary Commission was further complicated by oceanic boundary disputes. At stake were the San Juan Islands, which do not fall tidily into the 49th parallel designation. Joint occupation of the islands ended in 1872. At this time, German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm I, chief arbitrator in the dispute, sided in favor of the United States by setting the border at the Haro Strait. His decision cemented the final boundary between the United States and Canada.

Borders Don’t Create Territorial Sovereignty

At 1,933 miles, the southern border between the United States and Mexico is less than half the length of its border with Canada. Yet there have been no calls from the current administration to nullify this shorter political border, or to annex Mexico. Instead, tax dollars are being used to create physical barriers at the southern border including buoy sensors, fences, and walls. Federal officials estimate that “85 miles of new border wall is expected to go up this year with plans for hundreds of miles more in 2026 and beyond.”7

Both Canada and Mexico have been long-time allies with the United States, yet one border is deemed by the current administration to be almost immaterial, while the other border is being materially strengthened. The divisive and uneven stance towards these bordering nations is disrespectful, short-sighted, and ultimately self-destructive.

According to University of Pennsylvania Law Professor Beth Simmons, territorial sovereignty is created internally rather than externally. This means that laws and other forms of control work best inside a country rather than on its fringes. Borders are shared spaces, so border policies that focus almost exclusively on perceived security threats with shows of force, suspicion, and aggression towards those that attempt to cross them legally or illegally, are inhumane and counter-productive.

The Trump administration weaponizes border regions, creating an atmosphere of fear and escalating tensions along them. When operating in this detrimental mindset, the border emerges as a gate that locks people in and out. Simmons, however, likens border regions to bridges. She envisions borders as “cooperative institutions to which states have consented to avoid international conflict”8 by working in concert with one another for collective interests, connection, and security.

Another apt metaphor for Simmons convictions about borders is a see-saw; a game of balance where back and forth motion between participants is mutually beneficial. Fittingly, in 2020, the winner of the London Design of the Year Award was a collection of pink see-saws called the Teeter Totter Wall. The see-saws were the inspiration of two California professors of design and architecture, Virginia San Fratello and Ronald Rael. San Fratello and Rael positioned the see-saws so that they straddled a portion of the steel border fence that separates El Paso, Texas from Ciudad Juarez in Mexico. The see-saw creators “said they hoped the design would help people reassess the effectiveness of borders and encourage dialogue rather than division. ‘We have to think about how we can be connected and be together without hurting each other’ said San Fratello.”9 Families from both countries that joyously interacted with one another on the see-saws proved that common ground at the border can be easily established.

International Borders are Better Managed Cooperatively

To reduce our international borders to artificial, territorial lines of sovereignty, commerce, and transit is to dehumanize them. Borders are inherently permeable. For over 200 years, citizens in the United States and Canada, for example, have operated under the principles of good neighborliness in international relations. This means that governance decisions primarily have been “based on general aspects of morality, tolerance, and abstention from any action that would harm the interests of other parties.”10 The good will and relational ties that exist in borderlands, particularly among long-term allies, should not be underestimated.

Currently, “Washington [state] has 13 land border crossings along the 427 miles it shares with British Columbia.”11 The Peace Arch-Douglas Border Crossing off I-5 North in Blaine is one of the most popular of these land crossings. Blaine is a charming border town with a quaint downtown core where you can dine in a railway car, take a Sasquatch selfie, or grab fresh milk or ice cream from a local dairy. Its pleasant waterfront trails have stunning views of Mt. Baker and White Rock, B.C., part of metro Vancouver, which looms across the Salish Sea like the Emerald City in the Wizard of Oz . People who live in Blaine are salt-of-the-earth types who will stop to help a stranger with a flat tire and wait to leave until after the tow-truck arrives.

Border towns like Blaine have a personal investment in their Canadian neighbors. Many Blaine businesses rely on Canadian tourism; but beyond revenue, they consider Canadians to be their friends. Groups such as the Raging Grannies and Indivisible Bellingham (Bellingham is a large city adjacent to Blaine), have been holding pro-Canadian rallies at the Peace Arch since the Trump administration began targeting Canada with tariffs and annexation threats.

Though these rallies began with a handful of attendees, the frequency of them has quickly grown, as has the number of participants. On March 29th, for instance, well over a hundred Americans and Canadians gathered to affirm their bonds with one another and to commiserate about the damaging effects of policy changes towards Canada advanced by the Trump administration.

A handshake ritual was the culmination and highlight of the rally. Americans and Canadians lined up and faced each other like sports teams at the end of a game. The mood grew very emotional, with choked tears, hugs, and apologies as people moved down the line to personally greet one another.

A border may be a political and geographic terminus where one city, county, state, or country ends and another begins. But the camaraderie and caring amongst strangers at the rally demonstrated that human emotions of love, trust, and friendship transcend these boundaries. There was nothing fake or artificial in the mixed, raw emotions of outrage, dismay, shame, kinship, and apprehension displayed by both Americans and Canadians at the Peace Arch on March 29th. These reactions were a healthy response to policies deliberately designed to damage the harmony that exists among people on both sides of the border rather than to positively maintain their international bonds. To callously disregard the human element of a border in favor of territory demarcation and heightened security zones is to default on obligations of human rights and international stability. This approach wholly ignores the interdependence of borderlands and their potential as a resource for common good.

Works Cited

- “Peace Arch Historical State Park History,” Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, last accessed March 2025, https://parks.wa.gov/about/news-center/field-guide-blog/peace-arch-historical-state-park-history.

- Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, March 2025.

- Paul Kuenker,”One Hundred Years of Peace: Memory and Rhetoric on the United States/Canadian Border 1920-1933,” University of New Mexico, last accessed March 2025, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/151582898.pdf.

- Haley Chi-Sing, “Trump Downplays Canada’s Liberal Lean from Oval Office, Calls Border an ‘Artificial Line,’” Fox News, March 21, 2025, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/trump-downplays-canadas-liberal-lean-from-oval-office-calls-border-artificial-line.

- “USA-Canada Border Crossings,” Canada DUI Entry, 2025, https://www.canadaduientrylaw.com/border-crossings.php#:~:text=Washington%20State%20has%2013%20land,Lynden%20Aldengrove%2C%20and%20Sumas%20Huntingdon.

- Marcus Baker, “Survey of the Northwest Boundary of the United States, 1857-1861,” Department of the Interior, 1900, p. 27, https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0174/report.pdf.

- William La Jeunesse, “Trump Admin Shares Border plans for 2025 and Beyond: ‘As Much Wall as We Need,’” MSN News, April 2, 2025, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/trump-admin-shares-border-plans-for-2025-and-beyond-as-much-wall-as-we-need/ar-AA1Cb1St?ocid=BingNewsSerp.

- Beth Simmons, “International Borders: Yours, Mine and Ours,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, last accessed March 2025, https://legal-forum.uchicago.edu/print-archive/international-borders-yours-mine-and-ours.

- Lanre Bakare, “Pink See-Saws Across US-Mexican Border Named Design of the year 2020,” January 18, 2021, Guardian News, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/jan/19/pink-seesaws-across-us-mexico-border-named-design-of-the-year-2020.

- Dumitiria Floria and Narcisa Gales, “Affirming the Principles of Good Neighborliness in International Relations,” Logos Universality Mentality Education Novelty: Law, 8(2), p.4, doi:10.18662/lumenlaw/8.2/40.

- Canada DUI Entry, 2025.

Additional Resources

https://www.historylink.org/File/9194

https://www.historylink.org/File/5224

https://www.peacearchnews.com/community/celebrating-sam-hill-and-the-peace-arch-2781215

https://bcparks.ca/peace-arch-park/#facilities

https://www.thenorthernlight.com/stories/multiple-rallies-scheduled-at-peace-arch,37671.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/treaty-of-ghent